P.T. Barnum’s rise to fame is an emblematic reflection of the deeply entrenched inequalities of 19th-century America. Barnum, known as the “Great American Showman,” capitalized on the public’s thirst for spectacle and curiosity, transforming the entertainment landscape with his audacious displays of oddities and curiosities. He is often remembered for founding what became “The Greatest Show on Earth,” an early precursor to modern circuses. However, Barnum’s reputation is not without controversy; his genius for marketing and self-promotion often overshadowed the darker aspects of his rise to fame. He manipulated the public’s fascination with the exotic, the unusual, and the marginalized, profiting from the dehumanization of individuals, particularly those who were powerless or viewed as “other” by mainstream society. At the core of Barnum’s success lay a strategy that blurred the line between entertainment and exploitation, challenging the moral boundaries of his time and leaving a legacy that forces us to confront the racial and social hierarchies that sustained his fame.

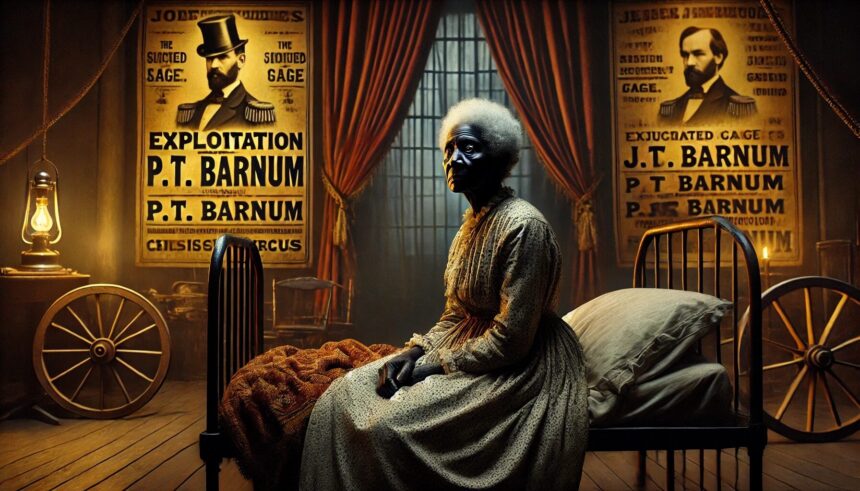

It is crucial to acknowledge that P.T. Barnum’s rise to fame was not solely due to his innovative circus acts or his ability to dazzle audiences with grand spectacles. His ascent was, in fact, deeply intertwined with the exploitation of marginalized and vulnerable individuals, particularly enslaved people. One of the most significant—and often overlooked—chapters of Barnum’s early career involved his cruel manipulation of Joice Heth, an elderly Black woman whom Barnum purchased and paraded as the 161-year-old former nurse of George Washington. Heth’s exploitation not only exemplified the intersection of racism and entertainment but also laid the foundation for Barnum’s fame. Long before the bright lights of the circus tent, it was the brutal commodification of an enslaved woman that propelled Barnum into the public consciousness, marking the beginning of his controversial legacy.

Joice Heth: The “First” Barnum Sensation

The story of P.T. Barnum’s purchase of Joice Heth underscores the profound exploitation at the root of his rise to fame. In 1835, Barnum bought the rights to exhibit Joice Heth, an elderly Black woman whom he cruelly branded as the 161-year-old former nurse of George Washington. Heth, already frail and likely blind and paralyzed, was displayed to the public as a living relic of early American history. Barnum’s fabrication of her age and historical importance captured the public’s imagination, drawing crowds eager to witness what was portrayed as a human link to the nation’s founding.

Heth’s role in Barnum’s career was pivotal. She became his first major attraction, and the profits generated from her exhibition allowed Barnum to build his fortune and establish his reputation as a master showman. Yet, Heth was not merely a stepping stone in his career; she was a clear example of how Barnum’s success was built on the dehumanization and objectification of enslaved individuals. Through relentless public display, Barnum commodified Heth’s body and life story, turning her suffering into spectacle for financial gain. Her death did not even mark the end of this exploitation, as Barnum continued to profit from a public autopsy meant to dispel rumors about her authenticity, further demonstrating how the cruel use of enslaved individuals like Heth was central to Barnum’s early success.

The significance of P.T. Barnum’s exploitation of Joice Heth is a revealing moment in America’s history of racial and social inequalities. In 1835, Barnum marketed Joice Heth as an astonishing human curiosity, claiming she was 161 years old and had been the nurse of George Washington. This outrageous fabrication was not only a reflection of Barnum’s flair for sensationalism but also an insidious use of racial and historical narratives to captivate a largely white audience.

Barnum advertised Heth as a living piece of early American history, fabricating documents and letters to support his claims about her alleged connection to George Washington. Her supposed age and role as a caregiver to the first president gave her an aura of national significance, turning her into a public spectacle. The public was eager to witness what was presented as a human link to America’s past, particularly one that confirmed sentimental ideas of the “loyal” Black slave in service to the nation’s founders. Heth’s body became the object of fascination, and her age, race, and fabricated story were exploited as Barnum’s masterful publicity stoked curiosity and controversy.

Through pamphlets, posters, and newspaper stories, Barnum fueled interest in Heth’s appearances, charging admission fees to those eager to see her in person. This marketing strategy was a precursor to Barnum’s later success in transforming entertainment into a commercial empire. However, it was also a stark reminder of how the exploitation of Black bodies, through both slavery and racial stereotypes, served as a profitable tool for white men like Barnum in the pursuit of fame and fortune.

It is crucial to recognize the brutal conditions under which Joice Heth was displayed, highlighting the dehumanization at the heart of P.T. Barnum’s early success. Heth, a frail elderly woman, was often confined to a bed throughout her exhibition. Barnum’s marketing painted her as a spectacle to be marveled at, not only for her alleged age but for the very fragility of her body. She was presented as a living relic of the nation’s past, yet this guise masked the physical exploitation she endured.

Heth, reportedly blind and partially paralyzed, had little autonomy. Barnum subjected her to grueling public displays, sometimes for up to 12 hours a day, where she was forced to recount fabricated tales of her life as George Washington’s nurse to curious audiences. Her condition—emaciated, weak, and unable to care for herself—was leveraged as part of the spectacle, with her physical deterioration sensationalized to boost ticket sales. Audiences were not only invited to listen to Heth’s tales but to examine her body as evidence of her supposed age. Her value in Barnum’s eyes lay in her ability to draw crowds, and this profit-driven exploitation led to her being treated as little more than a sideshow object, with no regard for her comfort or dignity.

Joice Heth’s experience is emblematic of the racial exploitation that permeated Barnum’s career and American society more broadly. As an enslaved Black woman, her suffering was commodified and turned into public entertainment, underscoring the systemic racism that allowed Barnum to profit from her pain while simultaneously dehumanizing her in the eyes of his audience.

The public’s fascination with Joice Heth were a stark reflection of the social dynamics that allowed P.T. Barnum to rise to fame at the expense of marginalized individuals. The American public was captivated by Heth’s supposed age and her fabricated connection to George Washington. In a country still defining its national identity, the notion of a living link to the Revolutionary era proved irresistible. Barnum’s clever marketing played into this fascination, tapping into the public’s reverence for historical figures while feeding a morbid curiosity about Heth’s physical state.

Crowds flocked to see Heth, eager to witness what was presented as a living relic of America’s past. Barnum fueled this curiosity by exaggerating every aspect of Heth’s life and story. He claimed she had cared for young George Washington, and these tales, woven with patriotic nostalgia, drew widespread interest. The audience, largely white, found in Heth’s story a way to engage with the nation’s early history, but their fascination was laced with racial stereotypes that dehumanized Heth, reducing her to a curiosity rather than recognizing her as a human being.

Barnum’s use of Heth was groundbreaking in how it combined spectacle with sensationalism, a formula that would define his later career. The success of the exhibit brought Barnum his first real taste of public notoriety, and with it, financial success. Newspapers reported on Heth’s appearances, and public debates emerged over the legitimacy of her age, further increasing interest. Barnum masterfully manipulated the media coverage to maintain public intrigue, even going so far as to encourage rumors and controversies about her authenticity.

In this way, Joice Heth’s exploitation became the foundation of Barnum’s fame, positioning him as a master of public spectacle. But her story is also a chilling reminder of how racism and the commodification of Black bodies were woven into the very fabric of American entertainment. Barnum’s early notoriety rested not on his circus or his later acts, but on the calculated exploitation of an elderly, enslaved Black woman, whose life and suffering were turned into profit.

Dehumanization and Public Curiosity

It is critical to understand the tactics P.T. Barnum employed to attract attention to Joice Heth, particularly through outrageous and dehumanizing claims about her age. Barnum was a master of spectacle, and with Heth, he seized upon the American public’s fascination with both the bizarre and the historical. To maximize interest, Barnum fabricated a story that Heth was 161 years old and had been George Washington’s nurse, a claim so fantastical that it sparked immediate public curiosity.

Barnum’s approach to marketing Heth was rooted in both sensationalism and deception. He carefully crafted elaborate narratives about her past, complete with supposed documents and testimonies, to lend credibility to the story. Posters and newspaper ads heralded Heth as a “wonder of nature” and a living link to the Revolutionary War, ensuring that crowds would flock to see her. To further bolster his claims, Barnum arranged for Heth to tell audiences fabricated stories of her time with the Washington family. Despite her frailty and likely cognitive decline, Heth was coerced into performing her role as the ancient nursemaid, repeating stories designed to evoke nostalgia and awe.

Barnum also capitalized on public skepticism, encouraging debate over Heth’s authenticity. He understood that controversy would fuel ticket sales, so he did little to dispel doubts about her age, allowing rumors and conflicting reports to circulate. This created a media frenzy, with some believing in her supposed age and others casting doubt, but both camps were drawn to see Heth for themselves. Barnum even staged an elaborate public autopsy after Heth’s death, where doctors proclaimed she was not as old as he had claimed. Yet even this revelation was part of Barnum’s calculated publicity machine—by prolonging public interest through scandal, he maintained the momentum of his rise to fame.

Through these tactics, Barnum skillfully manipulated the public’s curiosity and thirst for spectacle. But this strategy came at the cost of Joice Heth’s dignity and humanity. Her body and her life were reduced to tools in Barnum’s profit-driven enterprise, exemplifying how the exploitation of enslaved Black individuals was not just tolerated, but commercialized for entertainment.

The media and public reactions to Joice Heth reveal not only the exploitation she endured but also the broader societal fascination with racialized spectacle in 19th-century America. P.T. Barnum understood the power of public curiosity, and he skillfully manipulated both the media and his audiences to increase ticket sales for Heth’s exhibition. His tactics transformed Heth into a symbol of morbid curiosity, exploiting the intersections of race, history, and public fascination with the exotic and grotesque.

The press played a significant role in amplifying Barnum’s sensational claims. Newspapers across the country reported on Heth’s supposed age and her connections to George Washington, often without questioning the veracity of the claims. Barnum fed the media a steady stream of fabricated stories, creating a cycle of speculation and intrigue that kept the public hooked. Reporters wrote articles that vacillated between awe and skepticism, further fueling the debate over whether Heth was truly 161 years old. This back-and-forth coverage only deepened public interest, as people felt compelled to see Heth in person and judge for themselves.

Barnum, ever the showman, encouraged this skepticism as part of his strategy. He knew that the more people doubted Heth’s story, the more they would be drawn to witness her for themselves. By feeding rumors, such as that Heth was a mechanical hoax or that she was not truly as old as claimed, Barnum turned controversy into a marketing tool. The more outrageous the claims or doubts became, the more tickets he sold. Crowds were eager to either confirm or debunk the claims, but regardless of their motivation, they were paying customers.

Barnum’s ability to manipulate the media extended beyond simple advertisements; he orchestrated a nationwide buzz that blurred the lines between fact and fiction. Even after Heth’s death, Barnum exploited public curiosity by arranging for her body to be autopsied publicly, another calculated spectacle designed to keep Heth—and Barnum—center stage. The media covered this final indignity, further entrenching Barnum’s reputation as the ultimate showman, while Heth, in death as in life, was denied her humanity.

Through this exploitation of public curiosity, Barnum not only enriched himself but also contributed to a culture that commodified Black bodies for profit and entertainment. The media’s eager complicity in perpetuating these narratives underscores the societal indifference to the dehumanization of enslaved individuals, and how racial spectacle was used to distract from the underlying exploitation at its core.

The post-mortem examination of Joice Heth was a chilling final act of exploitation in her life, underscoring the extent to which P.T. Barnum was willing to commodify human suffering for profit. After Heth’s death in 1836, Barnum, ever the opportunist, arranged for a public autopsy, turning what should have been a private moment of dignity into yet another grotesque spectacle. This examination, conducted in New York City and attended by hundreds of spectators, was designed to resolve the swirling controversy about her true age—yet even this, in Barnum’s hands, became part of his theatrical manipulation.

The autopsy, performed by Dr. David L. Rogers, revealed that Joice Heth was likely no older than 80, far younger than the 161 years Barnum had claimed. This revelation debunked Barnum’s elaborate story, but it was hardly a loss for him. In fact, the public dissection was orchestrated precisely to maintain Barnum’s hold on the public’s attention. By turning Heth’s death into a spectacle, Barnum ensured that even in her final moments, she would remain a profitable curiosity. Tickets were sold for the autopsy, and newspaper coverage amplified the event, ensuring that Barnum remained in the headlines. Rather than diminish his fame, the autopsy only fed into Barnum’s larger-than-life persona, reinforcing his status as the ultimate master of public entertainment.

Barnum had created a situation where, regardless of the findings, he would emerge victorious. Whether Heth was proven to be 161 years old or not, the spectacle itself was enough to sustain public fascination. The autopsy became an extension of Barnum’s strategy to keep his audiences perpetually curious and engaged. It was a cruel irony that even in death, Heth’s body was denied respect, continuing to serve as a commodity for Barnum’s gain.

This final act of dehumanization reflects the broader societal acceptance of racialized exploitation during Barnum’s era. Heth’s treatment—from the fabricated narratives about her life to the public display of her death—exemplifies how enslaved Black bodies were commodified, objectified, and used to entertain and titillate white audiences. Barnum’s capitalizing on Heth’s autopsy underscores how deeply entrenched racism and exploitation were in the foundations of American entertainment, revealing the dark side of a man celebrated for his showmanship but whose fame was built on the suffering and dehumanization of others.

The Legacy of Exploiting Human Lives

It is essential to view P.T. Barnum’s exploitation of Joice Heth within the broader context of the racialized entertainment that permeated 19th-century America. Barnum’s use of Heth as a human spectacle was not an isolated incident, but rather a reflection of a deeply ingrained practice of dehumanizing Black bodies for the amusement and profit of white audiences. Heth’s story illuminates how the legacy of slavery extended beyond the plantation into the realm of public entertainment, where the lives and suffering of enslaved people became commercialized for white consumption.

Barnum’s use of Heth exemplifies the ways in which enslaved individuals were commodified not just for their labor, but for their perceived value as curiosities and objects of fascination. His claim that Heth was 161 years old and her fabricated connection to George Washington allowed Barnum to exploit racialized narratives about Black servitude and loyalty, tapping into a white public’s desire for both entertainment and affirmation of the racial hierarchies that justified slavery. Heth, presented as an almost mythical figure, was stripped of her personhood and reduced to a mere symbol of historical spectacle. Her suffering, frailty, and age—whether real or invented—became tools for Barnum’s profit.

This exploitation mirrored a broader cultural trend in which the suffering and dehumanization of Black people were sanitized for public consumption. From minstrel shows that mocked Black life to the exhibition of so-called “human curiosities” in sideshows, the entertainment industry repeatedly used the bodies and lives of marginalized people to create spectacles that affirmed racial superiority and justified ongoing oppression. The entertainment derived from these spectacles was not innocent; it reinforced and normalized the idea that Black people were inherently “other,” existing to serve as amusements for the dominant white society.

Barnum’s commodification of Joice Heth also speaks to the economic incentives behind these practices. The profitability of showcasing Black bodies in dehumanizing ways—whether through spectacles like Heth’s exhibition or the broader system of racialized entertainment—underscored how deeply intertwined race and capitalism were in America’s development. For Barnum and others like him, the exploitation of enslaved individuals was a means to financial success, with little regard for the humanity of the individuals whose lives were turned into public spectacles.

Heth’s story reflects the broader societal devaluation of Black life during and after slavery. Her dehumanization for profit was not an aberration, but rather part of a larger pattern of exploitation that stretched from the slave auction block to the stages of American theaters and exhibitions. Barnum’s use of Heth as a spectacle exemplifies how racism and capitalism intersected to turn the suffering of Black individuals into a source of entertainment, reinforcing racial hierarchies and contributing to the long-lasting legacy of racial exploitation in American culture.

It is clear that P.T. Barnum’s exploitation of Joice Heth was a foundational moment that not only launched his career but also set the tone for the morally questionable tactics that would define his future acts. By capitalizing on Heth’s life and fabricating her connection to George Washington, Barnum perfected the formula of using spectacle, deception, and racial exploitation to draw crowds and make a name for himself in the entertainment industry.

The Heth exhibition was the first instance where Barnum realized the financial and social rewards of manipulating public curiosity through racialized spectacle. His success with Heth demonstrated how easily he could exploit the public’s fascination with the exotic and the unusual—particularly when it involved a marginalized, dehumanized individual. The financial windfall from Heth’s exhibition gave Barnum the capital and confidence to continue refining his showmanship, incorporating elements of sensationalism and spectacle that would become his trademarks.

The key to Barnum’s success lay in his ability to blur the line between truth and fiction, and his exploitation of Heth revealed his willingness to manipulate vulnerable individuals to maintain public attention. He learned that controversy, even when morally questionable, could drive ticket sales and increase his fame. This strategy became a central pillar of Barnum’s career, as he continued to craft exaggerated narratives and outrageous displays designed to shock and captivate audiences.

Heth’s exhibition also set a tone of commodification and dehumanization that would carry through in Barnum’s later acts. Whether showcasing physically disabled individuals, so-called “freaks,” or non-Western people as curiosities, Barnum’s entertainment empire was built on exploiting those who were marginalized, racialized, or seen as “other.” He tapped into a public appetite for spectacle that reinforced existing social hierarchies, using the bodies and lives of these individuals to both entertain and affirm the superiority of the white audiences who came to gawk.

Ultimately, Joice Heth’s exploitation was a turning point in Barnum’s career, demonstrating how racial and social exploitation could be commercialized to build a showbiz empire. This early event did more than just make Barnum famous; it set the ethical tone for his future acts and established a precedent for how entertainment could profit from the dehumanization of vulnerable individuals. Barnum’s legacy, while celebrated for its contributions to modern entertainment, is inextricably tied to the exploitation of marginalized people, a reality that forces us to critically examine the foundations upon which his success was built.

Other Known Cases of Barnum’s Use of Human Exhibits

It is important to recognize that while Joice Heth is the most prominent example of P.T. Barnum’s exploitation of an enslaved individual, she was not the only person whose life and body were commodified for his profit. Although other figures, such as General Tom Thumb and Chang and Eng, were not enslaved, they too were exploited under Barnum’s showmanship, their humanity reduced to spectacle for the entertainment and financial gain of white audiences.

General Tom Thumb, whose real name was Charles Stratton, was a little person whom Barnum discovered at the age of five and immediately transformed into a star attraction. Barnum crafted an elaborate persona for Stratton, exaggerating his age, dressing him in lavish costumes, and placing him in mock performances where he was forced to mimic royalty or historical figures. While Stratton was not enslaved, Barnum exerted complete control over his life and career, exploiting his physical difference to draw massive crowds and amass considerable wealth. Stratton became a global sensation, but his identity, like Heth’s, was shaped by Barnum’s relentless pursuit of profit, leaving little room for him to be seen as anything other than a living novelty.

Similarly, Chang and Eng Bunker, the famous conjoined twins from Siam (modern-day Thailand), were exhibited by Barnum as exotic wonders of nature. Although they were not enslaved, their racial and physical differences were key elements of their exhibition, reinforcing notions of the “exotic other” that were central to Barnum’s shows. Chang and Eng were subjected to intense public scrutiny, their bodies displayed for profit in a manner that dehumanized them and made them objects of fascination rather than individuals. Barnum’s manipulation of their image and lives highlights his willingness to exploit anyone who could be cast as unusual or different, particularly those who were non-white or physically distinct from the norm.

The cases of General Tom Thumb and Chang and Eng, along with Joice Heth, reveal a consistent pattern in Barnum’s career: the exploitation of marginalized individuals for entertainment, particularly those whose race, physical appearance, or perceived “otherness” made them valuable commodities in the eyes of the public. Though the legal status of these individuals varied—some enslaved, some free—their treatment by Barnum was marked by the same dehumanizing tactics, reducing them to mere attractions whose lives were manipulated for his fame and fortune.

This legacy underscores how Barnum’s success, while celebrated for its ingenuity, was built on the systematic exploitation of people who were considered different by society’s standards. Whether they were enslaved, disabled, or racially “othered,” Barnum’s exhibits were rooted in a spectacle that relied on the marginalization and dehumanization of vulnerable individuals for public amusement and profit.

Examining P.T. Barnum’s exhibits reveals a deeply ingrained pattern of racial and cultural exploitation that permeated his career. Barnum’s “freak shows” were built upon a foundation of dehumanizing those who were physically or culturally different, turning marginalized individuals into public spectacles for profit. This exploitation was not limited to physical anomalies; Barnum’s exhibitions capitalized on racial hierarchies and colonialist fantasies, reinforcing stereotypes that devalued non-white lives and cultures.

One of the most striking examples of this racial and cultural exploitation is Barnum’s exhibition of individuals from non-Western countries, presented as “exotic” and “primitive” in contrast to the supposed superiority of white Western civilization. Figures like Chang and Eng, the conjoined twins from Siam, were not just displayed for their physical difference but also as symbols of the “foreign” and the “other.” Barnum carefully crafted their presentation to play on the public’s fascination with the exotic and unfamiliar, reinforcing the idea that non-Western bodies were objects of curiosity and amusement. Though Chang and Eng were not enslaved, their treatment reflected the broader racial dynamics of the time, where people from colonized or non-European nations were seen as inherently inferior or strange.

Barnum’s exhibits of people like William Henry Johnson, billed as “Zip the Pinhead,” also underscore the racial exploitation at play. Johnson, a Black man with microcephaly, was presented as the “missing link” between humans and apes, playing into deeply racist theories of evolution and the supposed intellectual inferiority of Black people. Barnum’s marketing of Johnson as a “wild man” from Africa directly tapped into the racist notions of African people as primitive and subhuman. Audiences flocked to see Johnson, not just because of his condition but because Barnum’s spectacle played into their preconceived racial biases. His exhibit reinforced the idea that Blackness was inherently linked to animality and otherness, contributing to the dehumanization of Black people in American society.

The exploitation of racial and cultural difference in Barnum’s exhibits mirrors broader social trends of the 19th century, particularly during the era of slavery, westward expansion, and colonialism. Barnum’s freak shows were not merely entertainment; they were active participants in the construction of racial hierarchies, where the bodies of Black, Asian, Indigenous, and other non-white individuals were commodified to affirm white supremacy. Just as Joice Heth’s story was manipulated to satisfy white audiences’ fascination with slavery-era myths, Barnum’s broader exhibits reinforced cultural narratives that justified the ongoing marginalization of people of color.

The parallels between Barnum’s treatment of racialized figures and other performers in his freak show reflect a common strategy: to exploit perceived difference—whether racial, physical, or cultural—for the amusement of a white audience. Figures like Tom Thumb, though white, were still exploited for their physical difference, yet the layer of racial exploitation that Barnum imposed on non-white figures heightened the dehumanization they faced. Racialized bodies were not simply subjects of curiosity; they were used to reinforce the social order, where whiteness was the norm and anything outside of it was positioned as “freakish” or “abnormal.”

Barnum’s legacy, often celebrated for its showmanship, must also be critically understood as a legacy of racial and cultural exploitation. His success was built not only on the physical differences of his performers but also on the racial and cultural narratives that dehumanized and commodified non-white bodies. Barnum’s freak shows were a microcosm of broader societal values, where racial inequality was both performed and profited from, leaving a troubling legacy that forces us to confront the role of entertainment in the construction and maintenance of racial hierarchies.

It is essential to critically reflect on the complicated legacy of P.T. Barnum. While Barnum is often celebrated as a visionary who shaped American entertainment, pioneering the modern circus and captivating audiences with his flair for spectacle, this narrative cannot be divorced from the darker aspects of his career. His success was not only built on innovation but also on the systematic exploitation of enslaved and marginalized individuals whose lives were commodified for profit.

Barnum’s rise to fame began with the exploitation of Joice Heth, an elderly enslaved Black woman whom he paraded as a curiosity, fabricating her connection to George Washington to attract paying crowds. Her dehumanization and suffering were not anomalies but part of a broader pattern in Barnum’s career. He repeatedly exploited individuals whose race, physical difference, or perceived “otherness” made them easy targets for public spectacle. From Heth to figures like General Tom Thumb, Chang and Eng, and Zip the Pinhead, Barnum’s shows relied on dehumanizing those who did not fit into the normative ideals of race, body, or culture. He understood that his audiences were drawn to spectacle, particularly when it involved reinforcing stereotypes of racial or physical inferiority, and he masterfully manipulated this for financial gain.

The darker legacy of Barnum’s career forces us to confront the ways in which American entertainment, even in its formative stages, was built on the exploitation of marginalized individuals. His use of Black, Asian, and disabled bodies as public curiosities reflected and reinforced the racial and social hierarchies of 19th-century America. At a time when slavery and segregation defined the nation, Barnum’s shows capitalized on the public’s fascination with difference—particularly racialized and physical difference—while obscuring the humanity of those on display.

Barnum’s legacy, therefore, must be understood as both a pioneer in entertainment and as a figure whose success was intertwined with the systemic racism and exploitation of his time. His ability to transform human suffering into spectacle and profit leaves a troubling imprint on the history of American entertainment. While Barnum undeniably shaped the modern show business industry, bringing together elements of curiosity, theater, and spectacle, the cost of that success came at the expense of the most vulnerable individuals, whose lives were turned into public amusements. His legacy compels us to question how entertainment can both reflect and reinforce the racial and social inequalities of its time—and how we continue to wrestle with these issues today.

It is imperative to recognize that P.T. Barnum’s rise to fame and fortune was not solely the result of his genius for showmanship, but was fundamentally built on the exploitation of marginalized individuals. Barnum’s use of enslaved, disabled, and racially “othered” people—most notably Joice Heth—was not a mere footnote in his career, but rather a central component of his success. His ability to transform human suffering and difference into spectacle captivated audiences and provided the foundation for his financial and public triumphs. This exploitation was not an unfortunate side effect of his career; it was a deliberate strategy that he used to draw attention, generate controversy, and sustain the public’s interest.

Barnum’s legacy is often romanticized as that of a master entertainer who shaped American culture, but we must also remember the human cost of that legacy. His rise to prominence was intertwined with the dehumanization of Black people, people with disabilities, and non-Western individuals, whom he treated as commodities to be exhibited for profit. Barnum’s exploitation of Joice Heth, an elderly enslaved Black woman, laid the groundwork for his future success, and this act of racial and cultural exploitation should not be glossed over or excused as a product of its time. It was a conscious decision that contributed to the normalization of public entertainment rooted in the degradation of marginalized people.

By remembering this darker side of Barnum’s career, we confront the uncomfortable truth about how American entertainment—and indeed, much of American history—was shaped by the exploitation of the vulnerable. Barnum’s achievements cannot be separated from the individuals whose lives he commodified for his own gain. To fully understand his impact, we must acknowledge that his fame and fortune were built, in part, on reinforcing harmful racial and social hierarchies that continued to dehumanize marginalized communities long after the curtains closed.

In today’s cultural reckoning with historical figures, it is crucial that we hold both aspects of Barnum’s legacy in balance. His contributions to entertainment history are undeniable, but they are inextricably linked to the exploitation of the very people he used to build his empire. Remembering this exploitation alongside his achievements offers a more honest and nuanced understanding of the man and his legacy, ensuring that we do not celebrate his successes without also recognizing the pain and injustice that accompanied them.

This is an expansion of a previous article: