Chavez Ravine and Its Legacy

Chavez Ravine, nestled in the hills just north of downtown Los Angeles, was once a predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood, home to generations of working-class families. Its streets were lined with modest homes, many built by the residents themselves, reflecting the community’s resourcefulness and deep roots. The neighborhood thrived as a close-knit enclave where families supported one another, shared traditions, and maintained a rich cultural heritage. Children played in the dusty yards, while their parents cultivated gardens and worked in nearby industries. Despite its poverty, Chavez Ravine was a place of pride and belonging, embodying the spirit of resilience common among many Mexican-American communities in Los Angeles during the early 20th century.

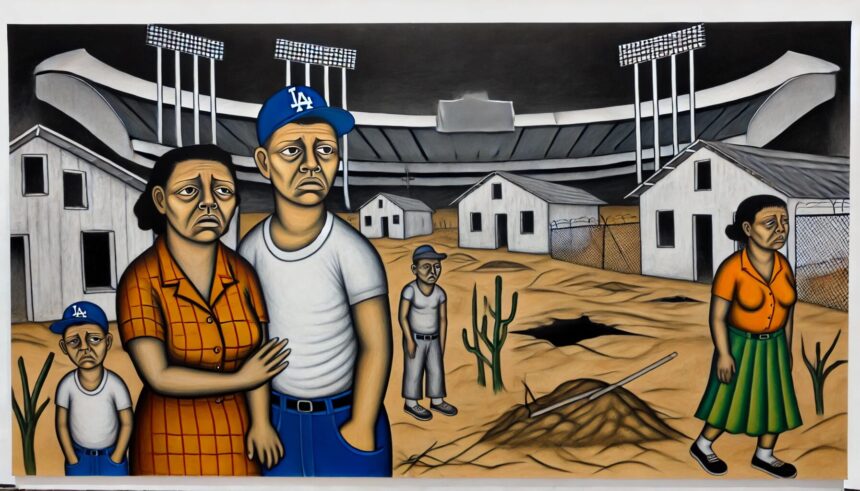

In the 1950s, Chavez Ravine became the target of a city-driven urban renewal project, initially framed as a plan to improve living conditions through public housing. However, under the guise of progress, the city invoked eminent domain, forcing families from their homes with promises of better housing that never materialized. Instead, the land was sold to private interests, ultimately leading to the construction of Dodger Stadium. The once-thriving neighborhood was demolished, and its residents were displaced, many left without compensation or the ability to return.

Dodger Stadium, completed in 1962, was built on the land where Chavez Ravine once stood, transforming a neighborhood into a symbol of corporate power and urban development. For the displaced Mexican-American families, the stadium represented not just the loss of their homes, but also the erasure of their community and culture. The emotional and psychological toll was profound, as former residents watched from afar while a major sports venue replaced their once-vibrant neighborhood. The construction of Dodger Stadium left a deep wound in the Mexican-American community, creating a legacy of distrust toward city officials and fueling ongoing struggles for housing justice and recognition of the displacement.

This article aims to delve into the history of Chavez Ravine, uncovering the political forces that led to its demolition under the guise of urban renewal. By examining the displacement of its Mexican-American residents and the subsequent construction of Dodger Stadium, the article sheds light on broader themes of racial injustice and the systemic use of urban renewal to displace communities of color in mid-20th century America. Through this lens, we explore how Chavez Ravine’s story reflects ongoing struggles for housing equity and the lasting impacts of such displacements on marginalized communities.

Origins of Chavez Ravine

Chavez Ravine was established in the early 20th century, with Mexican-American families settling in the area during the 1910s and 1920s. Many residents were immigrants or descendants of those who had come to Los Angeles seeking work in agriculture, railroads, and local industries. By the 1930s, Chavez Ravine had grown into a vibrant, self-sustaining working-class community, where families built their homes by hand, creating a close-knit neighborhood despite the lack of city services like paved roads or sewage systems. The community thrived culturally, with local schools, churches, and small businesses serving the predominantly Mexican-American population. Its residents, including prominent figures like María Ruíz de Burton and Manuel Arechiga, were resilient in their efforts to preserve the cultural identity and cooperative spirit of Chavez Ravine.

Chavez Ravine’s demographics in the early 20th century were predominantly Mexican-American, with families settling there as early as the 1910s and 1920s. These families were largely immigrants or descendants of those who arrived in Los Angeles seeking opportunities in agriculture, railroads, and industry. By the 1930s, the neighborhood housed roughly 300 families, most of them Mexican-Americans, living in modest, self-built homes. The residents were a mix of laborers, small business owners, and domestic workers, with strong cultural ties to Mexico. Families like the Arechigas and the Perezes became fixtures in the community, contributing to the tight-knit, cooperative atmosphere that characterized Chavez Ravine before its eventual displacement in the 1950s.

Daily life in Chavez Ravine during the 1930s and 1940s was deeply rooted in community and cultural traditions. Families like the Arechigas and Perezes worked together to maintain their modest homes, many built with their own hands. Children attended nearby schools, while parents labored in local industries or as domestic workers. Sundays were often spent at La Loma Church, a cultural and spiritual hub for the neighborhood. Residents celebrated Mexican holidays like Día de los Muertos and Cinco de Mayo with music, food, and community gatherings. Despite the lack of city services, Chavez Ravine thrived on mutual support and a strong sense of identity, preserving Mexican traditions and language while fostering a deep connection to the land and one another.

In the early 20th century, Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles faced widespread discrimination, segregation, and economic hardship. Following the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), many immigrants fled to the U.S., settling in areas like Chavez Ravine. By the 1920s, Los Angeles had the largest Mexican-American population in the country, yet they were often restricted to poor, underserved neighborhoods due to discriminatory housing policies like redlining. Despite these challenges, Mexican-Americans maintained a rich cultural presence in the city, forming tight-knit communities such as Boyle Heights and Chavez Ravine. These areas became cultural havens where residents preserved their language, traditions, and social networks, while also facing systemic barriers in education, employment, and public services. This broader context of exclusion and resilience shaped the experience of Mexican-American families living in Chavez Ravine until their forced displacement in the 1950s.

Promise of Urban Renewal: Public Housing Plans

In the late 1940s, Los Angeles city officials, led by housing advocate Frank Wilkinson, proposed an ambitious urban renewal project for Chavez Ravine. The plan was to transform the neighborhood into a modern public housing development called Elysian Park Heights, aimed at providing affordable housing for low-income families. The project, designed by renowned architect Richard Neutra, included 3,300 new units, schools, and parks. City leaders promised Chavez Ravine residents improved living conditions, citing the dilapidated state of their self-built homes. However, the promise of urban renewal soon unraveled as political opposition, driven by Cold War-era fears of socialism, derailed the project.

In the late 1940s, housing advocate Frank Wilkinson spearheaded the Elysian Park Heights public housing project, aimed at revitalizing Chavez Ravine. Alongside fellow advocates and architects like Richard Neutra, Wilkinson envisioned a modern housing complex with 3,300 units, designed to improve living conditions for low-income residents. The project included amenities like schools, parks, and playgrounds, intending to replace the dilapidated homes in Chavez Ravine with affordable, well-planned housing. The goal was to address the city’s growing housing crisis while integrating the displaced residents into the new development. However, the project became controversial as anti-communist sentiment grew, casting public housing as a socialist threat.

The residents of Chavez Ravine were promised modern homes and infrastructure as part of the Elysian Park Heights project in the late 1940s. City officials assured the community that their self-built, aging homes would be replaced with state-of-the-art public housing units, featuring modern amenities like electricity, running water, and sewage systems. The new development would also include schools, parks, and green spaces, offering a complete, improved living environment. These promises were intended to alleviate poverty and poor living conditions while ensuring that displaced families could return to better, more sustainable housing. However, these commitments were never fulfilled, leaving residents without the homes they were promised.

By the early 1950s, tension grew between housing advocates like Frank Wilkinson and powerful political and business leaders opposed to the Elysian Park Heights project. Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson, elected in 1953, led the opposition, fueled by anti-communist sentiment and pressure from private developers who saw greater profit in private real estate ventures. Business leaders and conservative politicians labeled public housing as a socialist initiative, and they argued that the city should prioritize private development over public welfare projects. This growing opposition, amplified by Cold War fears, ultimately led to the dismantling of the public housing plan, leaving Chavez Ravine’s residents caught between broken promises and the city’s shifting political landscape.

Politics of Displacement

During the McCarthy era in the early 1950s, anti-communist sentiment became a powerful force against public housing, including the Elysian Park Heights project in Chavez Ravine. Frank Wilkinson, the housing advocate leading the project, became a target due to his progressive views and connections to public welfare initiatives, which opponents branded as socialist. In 1952, Wilkinson was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and refused to testify, further fueling fears that public housing was linked to communist ideals. Politicians like Mayor Norris Poulson and private developers seized on this sentiment, using it to justify halting the project, arguing that government intervention in housing was a step toward socialism. This Red Scare-driven opposition ultimately led to the cancellation of the public housing plan, paving the way for private development and the construction of Dodger Stadium.

In the early 1950s, political maneuvering by Los Angeles city officials, led by Mayor Norris Poulson, played a crucial role in halting the Elysian Park Heights public housing project in Chavez Ravine. Elected in 1953 on an anti-public housing platform, Poulson capitalized on the growing fear of socialism during the McCarthy era, aligning himself with conservative business interests and real estate developers. Poulson worked to dismantle the public housing initiative, citing concerns over government overreach and advocating for private development instead. By 1959, the land originally acquired for the housing project was sold to Walter O’Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, to build Dodger Stadium, marking a decisive shift from public welfare to private commercial interests.

Starting in the late 1940s, Los Angeles officials used eminent domain to forcibly remove Chavez Ravine residents, claiming it was necessary for urban progress. The city labeled the area “blighted” and began acquiring homes in 1950 for the proposed Elysian Park Heights public housing project. Residents, many of whom had lived there for decades, were given modest compensation and promises of new homes, but by the early 1950s, those plans were abandoned. Under Mayor Norris Poulson’s leadership, the land was repurposed for Dodger Stadium. In 1959, the final eviction of the Arechiga family, widely publicized, saw police forcibly dragging residents from their homes, cementing the city’s narrative that the sacrifice of Chavez Ravine was for the greater good of urban development.

The use of police force during the evictions of Chavez Ravine reached its peak on May 9, 1959, when the Arechiga family, one of the last remaining residents, was forcibly removed from their home. The eviction, which had been brewing for years, culminated in a dramatic and highly publicized standoff. Los Angeles police officers dragged members of the Arechiga family, including elderly matriarch Aurora Arechiga, out of their home as news cameras captured the scene. These images of families being physically removed from their homes shocked the public and became a lasting symbol of the brutality behind the city’s displacement efforts, highlighting the deep human cost of the so-called urban renewal.

Aftermath: Dodger Stadium and the Loss of Community

In 1957, after years of political maneuvering, Los Angeles city officials, led by Mayor Norris Poulson, struck a deal to sell the Chavez Ravine land—originally intended for public housing—to Walter O’Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. O’Malley had been seeking a new location for his team, and the 352-acre Chavez Ravine site offered the perfect opportunity. The city transferred the land for a nominal sum, and by 1959, after the final evictions of families like the Arechigas, construction began. Dodger Stadium officially opened on April 10, 1962, symbolizing the city’s shift from public welfare to private enterprise, leaving behind the broken promises to the displaced Mexican-American community.

The displacement of Chavez Ravine families in the 1950s took an immense emotional and psychological toll on both the displaced residents and the larger Mexican-American community. Families like the Arechigas, who had lived in Chavez Ravine for decades, were forcibly removed, leaving behind not just homes, but a deep sense of cultural identity and belonging. The trauma of watching their neighborhood razed and replaced by Dodger Stadium in 1962 left many with feelings of betrayal and loss. For the broader Mexican-American community in Los Angeles, Chavez Ravine became a symbol of systemic injustice, where promises of urban renewal were broken and their community erased in favor of corporate interests. This deep wound fostered lasting mistrust in city officials and a sense of invisibility, as the cultural heritage of an entire neighborhood was sacrificed for profit.

Dodger Stadium, which opened on April 10, 1962, became a powerful symbol of broken promises for the former residents of Chavez Ravine and the wider Mexican-American community. The land, initially promised for public housing under the Elysian Park Heights project, was instead sold to Walter O’Malley to build the stadium. The construction erased the once-thriving, tight-knit neighborhood, where generations of families had lived and built their lives. The stadium’s gleaming presence stood as a stark reminder of the betrayal felt by those displaced, particularly families like the Arechigas, who were forcibly evicted. For the Mexican-American community, Dodger Stadium represented the prioritization of corporate interests over people, with the legacy of Chavez Ravine reduced to a footnote in the city’s pursuit of urban progress.

Despite the promises made during the forced evictions of the 1950s, the displaced residents of Chavez Ravine received little to no reparations or compensation. Families like the Arechigas, who had lived in the community for decades, were offered meager sums for their homes, often well below market value. By the time Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, many displaced families had been left struggling to find new housing. The city’s promises of providing public housing or fair relocation options were never fulfilled, leaving residents without adequate compensation for the loss of their homes, community, and cultural heritage. This lack of restitution deepened the sense of injustice and abandonment felt by the displaced Mexican-American community.

Broader Implications: Chavez Ravine and the Legacy of Urban Renewal

Chavez Ravine’s demolition in the 1950s was part of a broader pattern of urban renewal projects in mid-20th century America that disproportionately targeted communities of color. These projects, often justified as efforts to eliminate “blighted” neighborhoods, frequently displaced low-income, minority communities in cities across the country. Like Chavez Ravine, where Mexican-American families were uprooted for the construction of Dodger Stadium, similar projects in cities such as Chicago, Detroit, and New York also used eminent domain to clear land for highways, commercial developments, and sports arenas. These urban renewal initiatives, fueled by racial segregation and discriminatory policies, erased thriving communities of color under the guise of progress, leaving deep scars and widening racial and economic disparities.

Urban renewal in mid-20th century America often served as a tool for segregation and gentrification, disproportionately affecting communities of color. Beginning in the 1940s and accelerating through the 1960s, cities like Los Angeles, New York, and Detroit used urban renewal policies to clear so-called “blighted” areas, typically home to Black, Latino, and other minority groups. In Los Angeles, the demolition of Chavez Ravine in the 1950s mirrored similar actions nationwide, where eminent domain was used to displace residents, making way for developments that catered to wealthier, often white populations. This process effectively segregated cities by removing minority communities from valuable urban land, pushing them to more marginalized areas, while gentrifying cleared neighborhoods for commercial use or affluent housing, deepening racial and economic divides.

Racial and economic disparities that began with mid-20th century urban renewal policies, like the demolition of Chavez Ravine in the 1950s, continue to impact urban planning and housing policy today. Cities across the U.S. still grapple with the legacy of displacing communities of color for commercial developments, highways, and gentrified neighborhoods. Modern housing policies often perpetuate these inequalities, with minority communities facing higher rates of eviction, limited access to affordable housing, and displacement due to gentrification. In cities like Los Angeles, rising housing costs and insufficient protections for low-income residents mirror the injustices of the past, while racial segregation in housing remains a persistent issue. These disparities reflect the enduring impact of policies that prioritized development over the well-being of vulnerable communities.

Chavez Ravine’s demolition in the 1950s is just one example of urban renewal displacements that occurred across the U.S. during this era. In New York City, the construction of Lincoln Center in the 1950s displaced thousands of residents from the predominantly Black and Puerto Rican neighborhood of San Juan Hill. In Detroit, the development of the I-75 freeway in the early 1960s razed Black communities in the Paradise Valley and Black Bottom neighborhoods. Similarly, in Chicago, the construction of the University of Illinois at Chicago campus in the 1960s displaced the Italian-American community in the Near West Side. These projects, justified as urban progress, often destroyed thriving communities of color, deepening racial and economic inequalities nationwide.

The Memory of Chavez Ravine: A Community That Endures

Efforts to preserve the memory of Chavez Ravine have grown in recent years through books, documentaries, and oral histories. Notable works include Chavez Ravine, 1949 by Don Normark, a photography book that captures the community before its destruction, and Chavez Ravine: A Los Angeles Story, a 2003 documentary directed by Jordan Mechner, which explores the displacement through archival footage and interviews with former residents. Oral histories from families like the Arechigas, who were forcibly evicted, have been recorded to keep their stories alive. These efforts ensure that the legacy of Chavez Ravine and its vibrant Mexican-American community are not forgotten amidst the shadow of Dodger Stadium.

Dodger Stadium has made some efforts to reconcile its history with Chavez Ravine by acknowledging the displacement of its former residents. In 2021, the Dodgers unveiled a mural in Dodger Stadium’s Centerfield Plaza that honors the history of Chavez Ravine and the Mexican-American families who once lived there. The team has also hosted events commemorating the neighborhood’s legacy, and in some cases, former residents have been invited to share their stories. While these gestures aim to recognize the past, many feel they fall short of addressing the deep wounds left by the forced evictions and destruction of the community. The acknowledgment is seen as a step toward healing, but the legacy of the displacement continues to resonate deeply within the Mexican-American community.

Dodger Stadium has made efforts to acknowledge its complex history with Chavez Ravine, where the stadium now stands on land once home to a vibrant Mexican-American community. In recent years, the Dodgers have recognized this history through public gestures, such as the 2021 unveiling of a mural in the Centerfield Plaza that honors the former residents. The team has also held events where displaced families and their descendants have been invited to share their stories. While these efforts acknowledge the displacement, critics argue that they do not fully address the long-lasting pain and loss felt by the Chavez Ravine community, highlighting the continued need for broader recognition and reconciliation.

The displacement of Chavez Ravine has left a lasting impact on Mexican-American identity in Los Angeles, symbolizing the broader struggle against racial injustice and marginalization. The loss of the neighborhood is a painful reminder of the vulnerability of Mexican-American communities to displacement and erasure. This legacy continues to fuel activism for housing rights, as gentrification and rising rents in Los Angeles disproportionately affect Latino neighborhoods. Organizations like the East LA Community Corporation and Unión de Vecinos advocate for affordable housing, tenant protections, and community preservation, drawing on the memory of Chavez Ravine as a rallying point in the ongoing fight for housing equity and the protection of culturally significant communities in the city.

Lessons from Chavez Ravine

The story of Chavez Ravine holds deep historical and contemporary significance as a symbol of racial injustice and displacement. In the 1950s, the forced removal of its predominantly Mexican-American residents for the construction of Dodger Stadium reflected broader patterns of urban renewal projects that targeted communities of color. The neighborhood’s destruction represents the loss of a vibrant cultural enclave and highlights the systemic inequities that continue to shape housing policies today. Chavez Ravine’s legacy endures in the ongoing fight for housing rights, as it serves as a powerful reminder of the need to protect marginalized communities from exploitation and erasure in the name of progress.

Chavez Ravine teaches us critical lessons about racial injustice, housing inequities, and the politics of urban development. Its destruction under the guise of urban renewal reveals how communities of color have been systematically targeted and displaced in the pursuit of economic progress. The forced evictions highlight the deep-rooted racial inequalities in housing policies that persist today, where minority neighborhoods are often undervalued and overlooked. Chavez Ravine’s story underscores the need for more equitable urban planning that prioritizes the rights of residents over corporate interests, reminding us that progress should never come at the expense of marginalized communities.

Chavez Ravine’s story calls for ongoing vigilance in protecting vulnerable communities from displacement in the name of progress. As cities continue to grow and develop, there remains a risk that marginalized neighborhoods, like Chavez Ravine, will be sacrificed for commercial interests. It is crucial to ensure that urban development prioritizes equitable housing and community preservation over profit-driven projects. Policymakers and advocates must work together to safeguard these communities, uphold their rights, and prevent future displacements that erase cultural heritage and deepen social inequities. The lessons of Chavez Ravine remind us that true progress must be inclusive and just.

Sources and Further Reading

Books:

- “Chavez Ravine, 1949” by Don Normark (1999)

Normark’s photography book provides a vivid, intimate portrayal of Chavez Ravine before its destruction. His images, captured in 1949, offer a window into the daily lives of residents, showing a thriving, close-knit community. Normark’s photos became a critical resource for remembering the neighborhood after its demolition. - “City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles” by Mike Davis (1990)

This seminal book provides a broader context of Los Angeles’ history, including the role of urban development and displacement. Davis covers the Chavez Ravine story as part of his examination of the political and economic forces shaping the city, particularly its racial dynamics and housing policies. - “Dodgerland: Decadent Los Angeles and the 1977–78 Dodgers” by Michael Fallon (2016)

Although focused on a later period, Fallon’s book offers insights into the lasting significance of Chavez Ravine’s transformation into Dodger Stadium and its impact on the local community, as well as how it shaped Los Angeles’ identity. - “The Bulldozer and the Big Tent: Blind Republicans, Lame Democrats, and the Recovery of American Ideals” by Todd Gitlin (2007)

Gitlin includes a critical analysis of the Chavez Ravine saga within the broader civil rights struggles of the mid-20th century, focusing on the political and ideological battles over urban renewal and public housing.

Documentaries:

- “Chavez Ravine: A Los Angeles Story” directed by Jordan Mechner (2003)

This powerful documentary traces the history of Chavez Ravine through archival footage and interviews with former residents, including the Arechiga family, who were forcibly evicted. The film explores the cultural significance of the neighborhood and the lasting wounds left by its destruction. - “The Battle of Chavez Ravine” (PBS, 2005)

Part of the American Experience series, this documentary provides a detailed historical account of Chavez Ravine, focusing on the legal and political battles surrounding its destruction. It also includes interviews with historians and former residents, offering a comprehensive overview of the community’s displacement.

Articles:

- “The Displacement of Chavez Ravine: How the Dodgers Came to Los Angeles” – Los Angeles Times (April 10, 2012)

This article commemorates the 50th anniversary of Dodger Stadium’s opening and reflects on the displacement of Chavez Ravine residents. It includes interviews with former residents and explores the broader urban renewal policies that targeted low-income communities. - “Chavez Ravine, A Los Angeles Tragedy” by Eric Nusbaum – The Nation (May 2009)

Nusbaum’s article delves into the social, political, and economic forces behind the demolition of Chavez Ravine. It highlights the impact of Cold War politics, anti-communist sentiment, and corporate influence on the city’s decision-making. - “How Dodger Stadium Came to Be, and the Price Paid by Chavez Ravine Residents” – KCET (October 2019)

This article provides an in-depth exploration of the development of Dodger Stadium and the displacement of Chavez Ravine residents, featuring oral histories and personal accounts of the eviction.

Interviews and Oral Histories:

- “Chavez Ravine: Oral Histories of a Lost Community” – Los Angeles Public Library Oral History Program

This collection of oral histories captures firsthand accounts from former Chavez Ravine residents, including their memories of the neighborhood, the eviction process, and the legacy of their displacement. - Interviews with Frank Wilkinson

Wilkinson, the public housing advocate behind the Elysian Park Heights project, gave multiple interviews reflecting on the political and social struggles he faced during the Chavez Ravine saga. His perspectives offer critical insight into the intersection of housing policy and Cold War politics.

Academic Studies:

- “The Battle for Chavez Ravine: The Legal and Political Context of Eminent Domain in Postwar Los Angeles” by Becky Nicolaides – Journal of Urban History (2001)

This study provides an academic analysis of the legal framework and political forces that enabled the city of Los Angeles to displace Chavez Ravine residents using eminent domain. It contextualizes the evictions within the broader urban renewal movement of the 1950s. - “Segregation and the City: The Displacement of Minority Communities in Postwar Urban Renewal Projects” by Thomas Sugrue – American Historical Review (2007)

Sugrue’s work examines how postwar urban renewal projects across the U.S., including Chavez Ravine, disproportionately affected communities of color. It explores the racial motivations behind these policies and their long-lasting effects on minority neighborhoods.

These sources offer a comprehensive view of the history, cultural significance, and enduring legacy of Chavez Ravine, while also connecting it to broader civil rights and housing struggles in mid-20th century America.