Setting the Stage for Spectacle

The cobblestone streets of New York City, 1835, echoed with the clatter of horse-drawn carriages and the constant hum of merchants, hawkers, and onlookers. On every corner, something extraordinary vied for attention: from traveling entertainers juggling fire, to street preachers proclaiming salvation, to peddlers offering miracle cures. Yet amidst this cacophony, a new kind of spectacle was emerging—one that drew crowds like iron to a magnet. The people of New York, like much of America at the time, were captivated by curiosities—anything out of the ordinary, the bizarre, or the unnatural. Posters advertising strange wonders plastered walls, and word of mouth spread tantalizing whispers about oddities that had to be seen to be believed.

In this city, where the hunger for the extraordinary ran deep, a man named P.T. Barnum was about to make his first big mark. Barnum understood the pulse of the city, the thrill of something unknown or mysterious. And soon, the name Joice Heth, an elderly woman billed as the 161-year-old former nurse of George Washington, would be on everyone’s lips.

Phineas Taylor Barnum, barely in his mid-twenties, had the air of a man destined for greatness, even if he hadn’t yet found his path. Born into a modest family in Connecticut, Barnum had always been a natural storyteller, a quick thinker with an insatiable appetite for fame and fortune. The bustling streets of New York, with their constant swirl of people and possibilities, only fueled his ambitions. He had tried his hand at several businesses with varying degrees of success, but it was the world of showmanship that truly captured his imagination.

Barnum understood that people craved more than just entertainment; they wanted to be dazzled, to witness the extraordinary, and to marvel at the boundaries of the human condition. In this emerging world of “human curiosities,” where oddities, hoaxes, and spectacle could draw crowds by the thousands, Barnum saw his opportunity. He wasn’t just selling sights; he was selling stories, narratives that played on the hopes, fears, and imaginations of the masses. With a sharp eye for the unusual and a keen sense for what captured public interest, Barnum would soon turn his ambitions into reality, starting with a frail, elderly woman who he claimed had witnessed the birth of the United States itself.

The early 19th century was a time when America’s fascination with the bizarre and unknown reached a fever pitch. It was a nation in the midst of rapid growth, filled with curiosity about the world and eager to escape the ordinary. The Industrial Revolution was transforming daily life, and alongside it came a desire to explore the mysteries and oddities that lay beyond the mundane. People flocked to exhibitions that promised a glimpse of something extraordinary—whether it be strange animals, unusual humans, or artifacts from far-off lands.

Traveling sideshows, freak exhibitions, and so-called “human curiosities” became major draws in cities and towns alike, offering a mixture of entertainment, education, and shock value. Museums filled their halls with oddities, from preserved mummies to mechanical wonders. In this cultural moment, the lines between education, entertainment, and exploitation blurred, as the public’s thirst for spectacle knew no bounds. To many, it was a chance to step outside the bounds of reality, to question the limits of the natural world, and to confront the mysteries of life in an age of uncertainty. Barnum, ever the showman, recognized this hunger and seized upon it, knowing that the bizarre could captivate like nothing else.

The Arrival of Joice Heth

In 1835, P.T. Barnum made what he called a “sensational discovery”—an enslaved African-American woman named Joice Heth, whom he claimed was a living relic of America’s past. According to Barnum, Heth was no ordinary woman; she was said to be 161 years old and the former nurse of none other than George Washington himself. Barnum’s story painted her as a figure who had not only cared for the young Washington but had witnessed some of the most pivotal moments in early American history.

Barnum purchased Heth for the purpose of public exhibition, and he wasted no time turning her into a spectacle. Advertisements for her appearances boasted of her incredible age, her firsthand knowledge of Washington’s boyhood, and her connection to the founding of the nation. The idea of a living link to Washington, the most revered figure in American history, was irresistible to the public. Joice Heth became an immediate sensation, drawing crowds eager to see and hear from this supposed witness to a distant era.

But beneath Barnum’s carefully crafted narrative lay a troubling reality: Joice Heth was being used as a pawn in Barnum’s quest for fame and fortune, her humanity overshadowed by the myth he had built around her. Yet, for Barnum, this was the beginning of his career as a master of spectacle—a showman who could turn fiction into fact and profit from the public’s fascination with the extraordinary.

Barnum’s genius lay in his ability to craft stories that played on the hopes and imaginations of his audience, and Joice Heth was his first great myth. According to Barnum, Heth was not merely an elderly woman—she was the former nurse of George Washington, the most iconic figure in American history. Barnum claimed that she had cared for the infant Washington, cradling him in her arms, and had lived to tell the tale of his early years. This connection to the nation’s first president lent her an almost mystical air, making her not just a curiosity but a living link to America’s most sacred past.

In the burgeoning mythology surrounding the founding fathers, George Washington stood as a symbol of the nation’s ideals—strength, honor, and the triumph of democracy. Barnum knew that by tying Joice Heth to Washington, he was tapping into something far larger than a simple exhibition of human oddity. She became a symbol of history itself, a figure who had witnessed the birth of the nation and who now, miraculously, survived to tell the tale. For a public eager to connect with their country’s origin story, the opportunity to see someone who had, allegedly, known the father of the nation was too compelling to pass up.

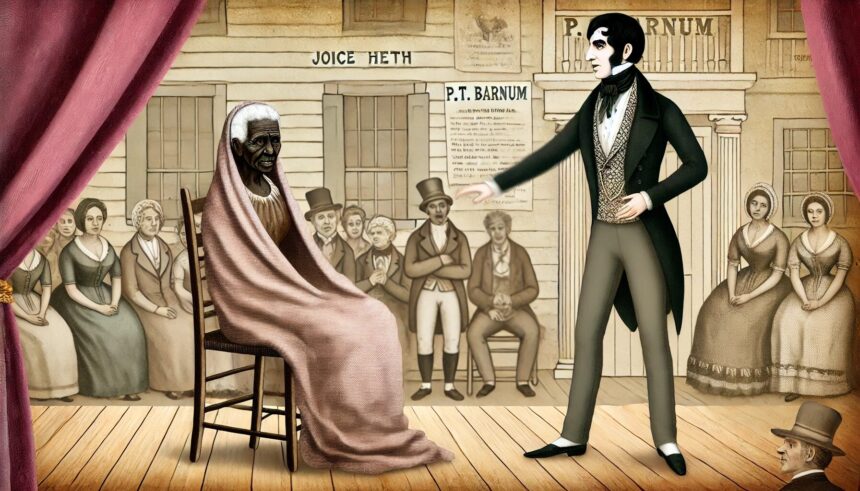

Joice Heth was presented to the public as a fragile, blind, and incredibly aged woman, her body bent with time and her voice barely more than a whisper. Wrapped in old blankets, she was seated in a simple chair, her frailty on full display for the curious eyes that gathered around her. Despite her physical state, Barnum insisted that she possessed a remarkable gift: the memories of a century and a half of life, including intimate knowledge of George Washington’s childhood.

Barnum would tell the audience that Heth had nursed the infant Washington, teaching him to walk and recounting stories of his early years—details no one else could know. Her blindness and weakness only seemed to heighten the aura of mystery and authenticity around her, as if time itself had kept her alive solely to share these stories. Her voice, though faint, was said to carry the weight of history. Barnum staged her appearances in such a way that she seemed to straddle two worlds—one foot in the present, the other in the distant past of American folklore and legend. Each performance was part history lesson, part fantasy, and all spectacle, designed to captivate the public’s imagination and deepen their fascination with this living link to the nation’s founding.

Barnum’s marketing genius lay in his ability to transform Joice Heth from a simple exhibition into a nationwide sensation. He flooded the streets with posters, each one proclaiming her extraordinary age and her intimate connection to George Washington. The posters featured bold, sensational headlines: “161 Years Old!” and “Nurse of the Immortal George Washington!” Barnum’s press releases described Heth in almost mythical terms, ensuring that the public was captivated long before they ever saw her.

He also cultivated relationships with local newspapers, feeding them tantalizing stories about Heth’s past and her miraculous longevity. Journalists wrote articles that blurred the line between fact and fantasy, quoting Heth’s supposed accounts of Washington’s boyhood. Interviews with Barnum were carefully staged, as he emphasized her authenticity and the rare opportunity for people to experience living history firsthand.

Every detail was meticulously orchestrated to stoke public interest and ensure packed audiences. Barnum understood that the more outlandish his claims, the more people would flock to see for themselves, whether out of belief or curiosity. Even skeptics found themselves paying the admission fee, eager to witness the spectacle and perhaps catch Barnum in a lie. In every sense, Barnum was a master of turning curiosity into profit, and Joice Heth was the key to his first great success.

Heth’s Exploitation and Popularity

Joice Heth’s life became a public spectacle as P.T. Barnum paraded her across the Northeast, exhibiting her in town halls, theaters, and private homes to audiences hungry for something extraordinary. She was billed as a living relic, the last surviving witness to the infancy of George Washington, and her exhibitions drew thousands of curious onlookers eager to catch a glimpse of history made flesh. From New York City to Boston, crowds gathered, paying their 50 cents to hear Heth recount stories of the nation’s founding father, her frail voice spun into the fabric of American folklore.

The exhibition was methodical, with Barnum presenting Heth in a way that amplified her otherworldly presence. Audiences would sit in awe as Barnum stood by her side, narrating her life and legacy while she nodded or offered faint replies. She was displayed as fragile yet wise, her blindness and weakened state only adding to her mystique. Barnum’s storytelling abilities elevated Heth from a simple curiosity to a figure of near-religious reverence, embodying an era long past. It didn’t matter that some doubted the validity of Barnum’s claims—her supposed connection to Washington was enough to pack the venues.

Each stop along the exhibition trail increased Heth’s popularity, and Barnum, ever the showman, ensured that every performance was covered by local press, further spreading the story. For months, Joice Heth’s life was no longer her own. She became the living embodiment of the public’s fascination with history, spectacle, and the blending of myth and reality. Though frail and in deteriorating health, Heth continued to be exhibited, her presence alone a ticket to Barnum’s early fame and fortune.

Joice Heth’s exhibition was more than just a spectacle of curiosity; it was a chilling reflection of the commodification of Black bodies in antebellum America. Under P.T. Barnum’s management, Heth’s life and identity were stripped down to a sideshow act, her humanity obscured by a fabricated narrative that turned her into a profitable attraction. As an enslaved woman, Heth had little agency over her own life, and even in her old age, she remained a pawn in the hands of those seeking to exploit her for personal gain.

Her body, frail and aged, became a canvas onto which Barnum painted his mythology—a living relic of a bygone era, a curiosity for the white audiences who came to gawk at her. This was a time when slavery and racial inequality were deeply embedded in the social fabric of America, and Heth’s exhibition was part of a broader system in which Black individuals were treated as property, their worth determined by what they could provide to others. For Barnum, Heth’s supposed connection to George Washington turned her into a product that he could sell to audiences, cashing in on both the public’s fascination with history and its insatiable desire for entertainment.

This exploitation was not unique to Barnum’s showmanship. The practice of putting Black bodies on display, often under false pretenses, was a common feature of 19th-century American entertainment. From so-called “freak shows” to the display of enslaved individuals in public auctions, Black men and women were commodified, their humanity reduced to spectacle. Heth’s story, then, was part of a larger legacy of racial exploitation—a system where the suffering and exploitation of Black people were masked by the veneer of entertainment.

Heth’s exhibition also speaks to the intersection of race and curiosity in a society that found fascination in the exotic and the “other.” Audiences came not just to see a connection to George Washington but to satisfy a curiosity about the body of an elderly Black woman, portrayed as both relic and oddity. Barnum’s ability to turn Heth into a profitable enterprise played on the racial dynamics of the time, where curiosity about Black lives was often intertwined with a sense of superiority and a willingness to exploit those lives for personal gain.

Ultimately, Joice Heth’s life was commodified, her exploitation veiled under the guise of public curiosity and historical intrigue. In Barnum’s hands, she became an instrument of profit, a tool to stoke the imagination of a public that rarely paused to consider the human cost of their entertainment. The intersection of slavery, race, and spectacle that marked her exhibition serves as a poignant reminder of the ways in which Black lives were objectified and dehumanized in antebellum America.

The exhibition of Joice Heth marked the beginning of P.T. Barnum’s rise to fame and solidified his reputation as a master of public deception and curiosity. With Heth, Barnum learned how to manipulate public perception, drawing enormous crowds not just to see her but to experience the fantastical narrative he had created. His ability to turn a frail, elderly woman into a national sensation demonstrated his flair for crafting stories that blurred the line between truth and spectacle, a skill that would become the cornerstone of his career.

Barnum’s genius lay in his ability to keep audiences guessing, always adding a layer of mystery or controversy to his exhibitions. With Heth, he wove a narrative so extraordinary—claiming she was 161 years old and the former nurse of George Washington—that it didn’t matter whether people believed it. The spectacle was in the possibility, the doubt, and the curiosity. Some came to marvel, others to debunk, but all paid for the chance to witness it for themselves. This balance between belief and skepticism became Barnum’s signature, allowing him to profit from both the curious and the critical.

The press took notice, and Barnum quickly learned how to leverage media coverage to his advantage. By feeding stories to local newspapers and providing interviews that stoked public intrigue, he ensured that the controversy surrounding Heth only added to her allure. The more outlandish the claims, the more people flocked to see her, and the more Barnum’s name spread across the country.

In the end, the exhibition of Joice Heth did more than make Barnum money—it made him famous. He became known not just as a showman but as a master manipulator of public perception, someone who could turn a hoax into a phenomenon. This early success set the stage for Barnum’s future endeavors, establishing him as a pioneer of modern entertainment, where the spectacle of the unknown could be far more captivating than the truth itself. Heth’s exhibition may have been his first major deception, but it certainly

The Death of Joice Heth

By early 1836, Joice Heth was nearing the end of her life. Exhausted from constant travel and public exhibition, her frail body could no longer withstand the relentless demands Barnum had placed on her. She had become a spectacle in every sense, a source of fascination and profit, but at a great personal cost. Her health deteriorated rapidly as she continued to perform, and in February of that year, she passed away.

But even in death, P.T. Barnum was not finished with Joice Heth. Ever the opportunist, Barnum saw one final way to capitalize on her story. He announced that Heth’s death was not the end of her tale—it was an opportunity to prove, once and for all, whether his extraordinary claims about her age had been true. Barnum, always the master of public curiosity, arranged a public autopsy of Joice Heth’s body, charging an admission fee to those eager to witness the final chapter of this strange and morbid spectacle. Even in her last moments, Heth’s life—and now her death—remained a commodity in Barnum’s hands.

Barnum promised the public that Joice Heth’s autopsy would finally reveal the truth behind her extraordinary age. For months, he had claimed that she was 161 years old, the former nurse of George Washington, and now, in death, science would confirm or disprove these sensational assertions. Barnum advertised the autopsy as the ultimate spectacle, where the mystery surrounding Heth’s age could be unraveled before a paying audience. For 50 cents, curious onlookers could watch as medical professionals examined her body, hoping to verify Barnum’s claims. It was a final, morbid promise: that the truth about this “living relic” of history would at last come to light.

The public autopsy of Joice Heth transformed what should have been a private moment into a macabre spectacle. Barnum masterfully turned the scientific examination of her body into an event that fed the public’s morbid curiosity. What had begun as a fascination with Heth’s supposed age and her connection to George Washington had now become a feverish desire to uncover her secrets in death. Crowds clamored for the chance to witness the autopsy, eager to see whether Barnum’s claims would be proven true or exposed as yet another grand deception.

The event, held in a New York City saloon, was less about science and more about the public hunger for answers—and for spectacle. Barnum had positioned the autopsy as the final chapter in Heth’s extraordinary story, and for many, the chance to observe her body laid bare seemed like the culmination of their fascination. They were not simply interested in medical truth; they wanted to be part of the sensational narrative that Barnum had woven. In their eyes, the autopsy was an opportunity to peel back the curtain on a mystery that had captivated the nation.

As the medical examiner began his work, the crowd leaned in, hoping to glimpse something extraordinary—some evidence of the supernatural age that Barnum had promised. The spectacle of science was now in full swing, blending medical examination with theatrical showmanship, as the public’s curiosity morphed into a grim desire to uncover the physical proof of Heth’s fantastical life story.

The Autopsy and Aftermath

The autopsy of Joice Heth, performed before a captivated audience on February 25, 1836, revealed the truth that many had suspected but few dared to believe: Heth was not 161 years old as Barnum had claimed, but likely around 80 years old. The medical examiner found no evidence to support Barnum’s fantastical narrative. Her body showed the typical signs of an elderly woman, but nothing that suggested she had lived more than a century and a half.

This revelation exposed Barnum’s grand tale as a hoax, unraveling the myth he had so carefully crafted. The public, who had paid to witness the event, now faced the truth that they had been deceived by one of the greatest showmen of their time. Yet, despite this exposure, Barnum’s reputation did not suffer. In fact, the scandal only added to his fame, proving that in Barnum’s world, even a hoax could be turned into an opportunity for greater success. The revelation that Joice Heth was not the ancient relic he claimed did little to diminish the spectacle he had created—it simply became part of Barnum’s legend as the ultimate manipulator of curiosity and belief.

The public reaction to the revelation of Joice Heth’s true age was a mixture of outrage and morbid fascination. Many felt deceived, realizing they had been duped by Barnum’s elaborate tale of a 161-year-old woman who had cared for George Washington. Some expressed anger, feeling they had been misled and made fools of for believing such an outlandish claim. These individuals saw the autopsy as the final proof that Barnum’s exhibition had been nothing more than a scam.

Yet, for others, the spectacle itself was worth the price of admission. Even in exposing the truth, Barnum had managed to captivate the public in a way few others could. They marveled at his audacity and his ability to turn deception into entertainment. In their eyes, the hoax was part of the show, a testament to Barnum’s genius as a showman. They recognized that Barnum had not just sold a story—he had sold an experience, one that blurred the line between reality and illusion. For these spectators, the spectacle of the autopsy was just as enthralling as the myth of Joice Heth, and Barnum’s ability to stir public curiosity remained unrivaled.

P.T. Barnum, ever the master of turning controversy into opportunity, wasted no time spinning the scandal surrounding Joice Heth’s true age to his advantage. Instead of retreating in shame after the autopsy revealed Heth to be around 80 years old, far younger than his claim of 161, Barnum embraced the exposure as part of the show. In typical Barnum fashion, he argued that the age discrepancy was all part of the act—a piece of theater designed to entertain and provoke curiosity.

He publicly declared that the real spectacle had always been in the debate itself, not the truth of Heth’s age. Barnum hinted that perhaps Heth’s age could never truly be known, and that the controversy only added layers to her mystique. With a sly grin and a wink, Barnum reminded the public that they had paid for entertainment, and entertainment they had certainly received. By deftly pivoting the conversation, Barnum transformed what could have been a damaging revelation into further press coverage, keeping his name in the headlines and ensuring that even a scandal only fueled his growing fame.

In the end, Barnum’s charm and unapologetic attitude helped him weather the storm, as he turned deception into art, maintaining his reputation as the ultimate showman who could make the ordinary extraordinary—and profit from it, scandal or not.

Legacy of Joice Heth and Barnum’s Career

The Joice Heth exhibition was a pivotal moment in P.T. Barnum’s career, marking the beginning of a lifelong mastery of manipulation, curiosity, and spectacle. Through Heth’s story, Barnum discovered a fundamental truth that would guide him for decades: people craved a good story more than they cared for the facts. The public’s willingness to believe—or at least entertain—the idea that Heth was a 161-year-old woman who had nursed George Washington proved that spectacle, emotion, and the power of suggestion were far more valuable than reality itself.

Barnum learned that audiences were eager to suspend their disbelief if the experience was captivating enough. The line between truth and fiction became irrelevant when the performance drew crowds and sparked conversations. This understanding allowed him to embrace bold deceptions throughout his career, using hype, imagination, and controversy to keep the public engaged. With Heth, Barnum had tested the limits of public gullibility and found that people were more than willing to play along, as long as the tale was entertaining.

From this exhibition forward, Barnum’s career was defined by his ability to blur the boundaries of fact and fantasy, whether it was with mermaids, giants, or elaborate hoaxes. He mastered the art of transforming curiosity into profit, recognizing that the greater the spectacle, the less important the truth became. The Joice Heth exhibition was not just his first great success—it was the foundation of his philosophy as a showman, teaching him that in the world of entertainment, the story was everything.

Joice Heth’s life and death, once the center of an extraordinary spectacle, quickly became a footnote in history, overshadowed by P.T. Barnum’s meteoric rise to fame. While Heth had been at the heart of Barnum’s first major exhibition, her own story—her humanity, her suffering, and her exploitation—was soon lost in the larger narrative of Barnum’s career. As Barnum went on to greater fame with larger shows and more elaborate hoaxes, Heth faded into the background, remembered only as the curious starting point for one of America’s greatest showmen.

Her legacy was consumed by Barnum’s, as his ability to spin stories, regardless of their truth, became the focal point of public interest. Heth herself was reduced to a symbol—a tool Barnum had used to learn the power of spectacle. The controversy over her age, her connection to George Washington, and the public autopsy became part of Barnum’s legend, but Heth’s own life, her experiences, and her exploitation were rarely discussed. She became one of many individuals whose lives were commodified for entertainment, her name and identity subsumed by the larger narrative of Barnum’s genius for publicity.

In the end, Joice Heth’s legacy was not her own. It was shaped and overshadowed by the man who profited from her story, leaving her as a forgotten figure in the shadows of American entertainment history. While Barnum’s name became synonymous with showmanship and spectacle, Heth’s life was largely erased, remembered only as the vehicle that launched his career.

The story of Joice Heth stands as a stark reminder of how the boundaries between entertainment and exploitation were often indistinguishable in early American show business. In the case of Heth, an elderly, enslaved woman was reduced to a spectacle, her life and identity commodified for the amusement of the public and the profit of P.T. Barnum. While Barnum marketed her as a historical marvel, the reality was far darker: she was exploited, her body and story manipulated to satisfy the public’s thirst for curiosity, with little regard for her dignity or humanity.

The Joice Heth exhibition highlights the troubling intersection of race, power, and spectacle in 19th-century America. As an African-American woman who had lived through the dehumanization of slavery, Heth’s exploitation under Barnum was a continuation of a broader societal pattern—one that treated Black bodies as commodities for white consumption. Her frailty and supposed connection to George Washington only intensified the public’s fascination, but beneath the spectacle was a deep ethical compromise that blurred the line between entertainment and cruelty.

This dynamic was not unique to Barnum’s time. The commodification of marginalized individuals in the name of spectacle continues to echo in modern entertainment, where reality shows, viral content, and media sensationalism often exploit vulnerable people for profit. The hunger for the extraordinary—whether in the form of human curiosities, scandalous lives, or personal suffering—still drives much of today’s entertainment industry. In Barnum’s time, as now, the focus on profit and spectacle often comes at the expense of ethical considerations, where the boundaries of exploitation are easily crossed in pursuit of a story that will captivate the masses.

The legacy of Joice Heth serves as a sobering reflection on how far society has come—or hasn’t—in confronting the exploitation that fuels entertainment. As we look back on her story, it is crucial to acknowledge not just the spectacle but the cost of that spectacle, and to question the systems that continue to blur the line between entertainment and exploitation in the modern age.

The Myth and the Man

P.T. Barnum’s early hoax with Joice Heth was a blueprint for the larger spectacles that would define his career and shape American entertainment. The success of the Heth exhibition taught Barnum valuable lessons about the power of illusion, storytelling, and the public’s willingness to embrace the extraordinary, even when confronted with obvious fabrications. This understanding of human curiosity became the foundation for Barnum’s future endeavors, including his famed American Museum and, later, his world-renowned circus.

In the American Museum, Barnum curated a collection of oddities, curiosities, and hoaxes that attracted visitors from all walks of life. He used the same tactics he had honed with Joice Heth—sensational advertising, provocative claims, and a blend of education and spectacle—to keep the public enthralled. Barnum understood that people came not just for the exhibits but for the experience of being dazzled, confused, and amazed. He masterfully walked the line between truth and fiction, drawing crowds with both genuine wonders and elaborate hoaxes.

This ability to manipulate public curiosity reached its peak with the creation of his circus, “The Greatest Show on Earth,” which combined human performances, exotic animals, and fantastical displays into a grand spectacle that captivated audiences around the world. Barnum’s early experience with Heth had taught him that people craved entertainment that blurred the boundaries between the possible and the impossible, and he used this insight to create an entertainment empire.

The hoax of Joice Heth foreshadowed Barnum’s lifelong success as the architect of American spectacle. By tapping into the public’s thirst for mystery and wonder, Barnum crafted an enduring legacy as the father of modern entertainment—a legacy that began with a simple, yet deeply influential, act of deception.

The story of Joice Heth, though mired in controversy and exploitation, has left a lasting imprint on American folklore. Despite being revealed as a hoax, her name continues to evoke curiosity, symbolizing a time when the lines between entertainment, deception, and human dignity were blurred beyond recognition. Joice Heth’s tale serves as a reminder of how easily lives could be manipulated for profit and spectacle, and how public fascination with the extraordinary can overshadow the humanity of those on display.

Heth’s legacy remains complex: she was at once a victim of exploitation and a central figure in the spectacle that launched P.T. Barnum’s career. Her life and death reflect the uncomfortable truth about how American entertainment was built on the commodification of marginalized individuals, yet she also stands as a testament to the enduring power of curiosity. Even today, Joice Heth’s story captivates those who seek to understand the darker intersections of race, exploitation, and showmanship in 19th-century America.

While Barnum’s name has become synonymous with spectacle and deception, Joice Heth’s story persists as a cautionary tale—a reminder that behind the curtain of entertainment, there are real people whose dignity and humanity should never be eclipsed by curiosity or profit.

This article has been expanded to focus on dehumanization for entertainment: