Palm Springs, nestled in Southern California’s Coachella Valley, has long been known as a luxurious desert oasis, renowned for its stunning landscapes, year-round sunshine, and reputation as a retreat for Hollywood celebrities and the wealthy. Boasting world-class resorts, golf courses, and mid-century modern architecture, the city presents itself as an idyllic getaway. Beneath this glamorous exterior, however, lies a deeper history of racial and economic segregation, where communities of color—particularly in areas like Section 14—faced systemic displacement and exclusion in favor of wealthy, predominantly white developments.

Section 14, located in the heart of Palm Springs, was a vital residential area for Black and Latino communities from the early 1900s to the mid-20th century. As Palm Springs grew into a tourist haven, Section 14 became one of the few places where non-white residents could live due to segregationist policies. This land, owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, became a haven for working-class families who helped build the city’s infrastructure. Despite its central location, Section 14 was excluded from the city’s glamorous image, and its residents were subjected to substandard living conditions, ultimately leading to a brutal campaign of forced evictions and demolitions in the 1950s and 60s, erasing much of its community and history.

This article aims to uncover the racial injustice behind the forced evictions and demolitions in Palm Springs’ Section 14, where Black and Latino families were systematically displaced in the mid-20th century to make way for urban redevelopment catering to the city’s wealthy, white elite. By exploring the history of Section 14, the article sheds light on the broader systemic issues of racial discrimination, urban planning, and the erasure of marginalized communities. It highlights how these patterns of exclusion were not isolated events, but part of a larger trend of economic and racial injustice deeply rooted in American urban development.

Historical Context of Section 14

Early Days of Palm Springs

Palm Springs was founded in the late 19th century, originally inhabited by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. Its transformation into a resort town began in the early 1900s, when the area’s dry, warm climate attracted visitors seeking relief from health conditions like tuberculosis. By the 1920s, Hollywood elites and wealthy vacationers began flocking to Palm Springs, drawn by its scenic desert backdrop, luxury hotels, and secluded atmosphere. Over the decades, the city evolved into a glamorous destination, with high-end resorts, golf courses, and exclusive neighborhoods, all catering to affluent, predominantly white tourists and residents, while segregating non-white communities like Section 14 to the city’s periphery.

Marginalized communities, including Black, Mexican, and Native American residents, played a crucial role in building Palm Springs. They provided the labor that helped construct the city’s resorts, homes, and infrastructure, often working as housekeepers, gardeners, and builders for the affluent white population. Despite their essential contributions, these communities were segregated into areas like Section 14, facing poor living conditions, limited resources, and exclusion from the city’s economic prosperity. Their labor was instrumental to Palm Springs’ rise as a luxury destination, but they were denied access to the wealth and amenities they helped create.

Establishment of Section 14

Section 14 was part of the ancestral tribal land of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, who had lived in the Palm Springs area for centuries. In the early 20th century, the U.S. government divided this land into a checkerboard pattern of alternating tribal and non-tribal ownership. Section 14, located in the heart of Palm Springs, remained under the tribe’s control and was leased to Black and Latino residents due to segregation laws that barred them from living in other parts of the city. Though centrally located, the land was developed into a low-income community, which became a vital home for Palm Springs’ marginalized populations.

Section 14 developed into a low-income, predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood in the mid-20th century, as Palm Springs’ segregation policies forced non-white residents to live in this area. Located just blocks from the affluent white neighborhoods and luxurious resorts, Section 14 housed the city’s working-class residents—many employed in service jobs for the wealthy. Despite its proximity to wealth, the neighborhood lacked basic infrastructure like paved roads, sewage systems, and adequate housing, existing in stark contrast to the opulent surroundings. It became a community of necessity, where marginalized groups built lives despite the city’s neglect and deliberate exclusion from Palm Springs’ prosperity.

Racial Segregation and Urban Planning

Segregationist policies in Palm Springs dictated where non-white residents, particularly Black, Latino, and Native American communities, could live. Restrictive housing covenants and discriminatory zoning laws confined these groups to areas like Section 14, while white residents enjoyed exclusive access to affluent neighborhoods. Non-white residents were prohibited from owning property or living in most of the city, forcing them into overcrowded, substandard housing in Section 14. These policies not only maintained racial segregation but also ensured that the marginalized communities remained isolated from the economic and social benefits of Palm Springs’ development.

The socio-economic divide between Section 14 and the surrounding affluent areas was stark. While nearby neighborhoods boasted luxury homes, manicured landscapes, and modern infrastructure, Section 14’s residents lived in substandard housing with limited access to basic services like paved roads, sewage, and running water. Wealthy white communities flourished with the economic benefits of Palm Springs’ tourism and resort development, while Section 14 remained impoverished, its residents largely employed in low-wage service jobs supporting the city’s elite. This glaring contrast symbolized the deep racial and economic inequalities entrenched in Palm Springs’ urban landscape.

The Evictions and Demolitions (1950s-1960s)

The City’s Push for Redevelopment

In the 1950s and 60s, Palm Springs sought to redevelop Section 14 to capitalize on its prime location for tourism and profit. City officials, pressured by business interests, viewed the predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood as “blighted” and undesirable, obstructing the expansion of luxury resorts and real estate developments. They saw financial opportunity in replacing the low-income community with upscale hotels, shopping centers, and vacation homes, which would cater to affluent tourists. This push for redevelopment prioritized economic gain over the rights and well-being of Section 14’s residents, ultimately leading to their forced eviction and the destruction of their homes.

Local white business interests in Palm Springs heavily pressured city officials to remove what they viewed as the “blight” of Section 14. These business leaders, eager to expand luxury tourism and real estate, saw the predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood as an eyesore incompatible with the city’s image of wealth and leisure. They pushed for its removal to make way for high-end developments that would attract more affluent visitors. Their influence led to city-backed plans to demolish the homes in Section 14, framing the community as a barrier to economic growth and progress, despite the harm it would cause to its residents.

Forced Evictions

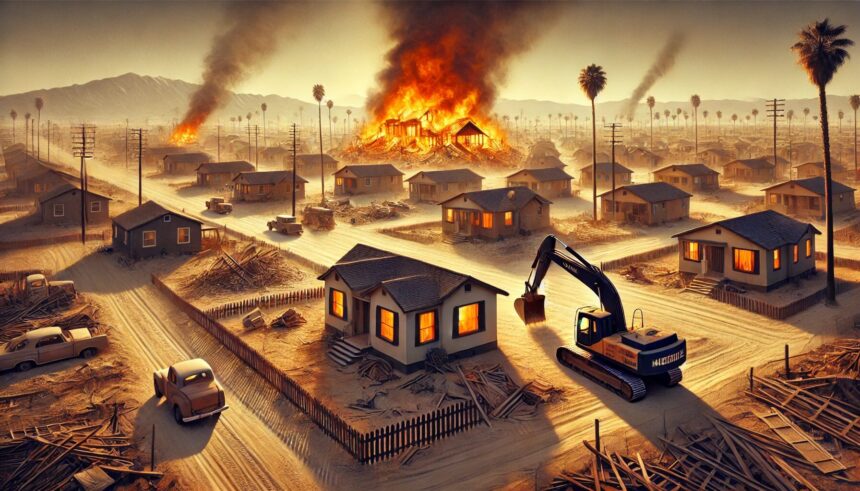

To force residents out of Section 14, the city of Palm Springs employed aggressive tactics, including threats, legal maneuvering, and even arson. Officials used code violations and legal pressure to intimidate residents, issuing eviction notices with little to no warning. Land leases were abruptly terminated, and homes were declared unsafe, despite the lack of city-provided infrastructure. In more extreme cases, arson was used as a covert method to drive families out—homes were mysteriously set on fire, leaving residents with no choice but to flee. These tactics were part of a coordinated effort to clear Section 14 for redevelopment, disregarding the rights of its marginalized inhabitants.

Black and Latino families in Section 14 faced heartbreaking displacement as their homes were destroyed. Many had lived in the neighborhood for decades, building close-knit communities despite limited resources. Families recalled the sudden shock of eviction notices, often receiving only days to leave. Some returned from work to find their homes reduced to rubble or engulfed in flames, with their belongings destroyed. Others described the emotional toll of watching bulldozers tear down their houses while city officials stood by, indifferent. These personal stories reflect the trauma of losing not just property but a sense of safety, stability, and community, as entire neighborhoods were erased to make way for wealthier developments.

Demolition of Section 14

The destruction of homes in Section 14 was swift and brutal. Bulldozers arrived with little warning, leveling entire blocks of houses as families scrambled to gather their belongings. In some cases, homes were reduced to rubble in a matter of hours. The use of fire was equally devastating—several homes were mysteriously set ablaze, leaving families displaced and with nothing. These fires often broke out at night, forcing residents to flee for safety. The coordinated demolition and arson erased the neighborhood, leaving a barren landscape where a vibrant community once stood, clearing the way for the city’s redevelopment plans.

The erasure of Section 14 inflicted deep trauma on the community. Families who had built their lives there for decades were suddenly uprooted, losing not only their homes but also their sense of belonging and security. The forced evictions, demolitions, and fires shattered the social fabric of the neighborhood, severing close-knit relationships and displacing people into unfamiliar and often inhospitable environments. For many, the experience was a profound loss—of stability, generational wealth, and cultural identity. The psychological scars ran deep, as the destruction symbolized not just physical displacement, but the city’s blatant disregard for their humanity.

Legal and Political Battle

Legal Struggles of the Evicted

Section 14 residents attempted to fight back through the courts, filing lawsuits to challenge their evictions and the destruction of their homes. They argued that the city’s actions violated their rights, particularly targeting the lack of due process and the racially discriminatory nature of the evictions. Despite their efforts, the legal system often sided with the city, using technicalities and land use laws to justify the demolitions. Residents faced an uphill battle, with limited financial resources to sustain prolonged legal fights against powerful city officials and developers, ultimately leaving many without recourse as their community was dismantled.

Residents of Section 14 brought several lawsuits against the city of Palm Springs, aiming to stop the forced evictions and demolitions. These legal challenges argued that the city violated their property and civil rights, using racially discriminatory tactics to clear the area for redevelopment. The lawsuits sought compensation for the destruction of homes and raised concerns about due process, as many evictions occurred without proper notice or legal grounds. However, the courts often ruled in favor of the city, citing zoning laws and land-use regulations. These rulings left most residents without compensation or a path to return, further entrenching the injustice.

Role of Civil Rights Leaders

National civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and local activists became involved in advocating for Section 14 residents as the evictions gained attention. Dr. King publicly condemned the racial injustice happening in Palm Springs, calling for action against the systemic displacement of Black and Latino families. Local figures, such as Ralph Abernathy and other community leaders, organized protests, held rallies, and worked with legal teams to challenge the city’s actions. Their involvement helped bring national awareness to the plight of Section 14, framing it as part of the broader civil rights struggle against housing discrimination and racial inequality in America.

Tribal Land Ownership and the Role of the Agua Caliente Tribe

The relationship between tribal sovereignty and Palm Springs’ redevelopment efforts was complex. Section 14, as part of the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians’ land, was subject to federal trust protections, but the tribe leased the land to Black and Latino residents. The city exploited this arrangement, leveraging the tribe’s limited control over land use decisions to push redevelopment plans. While the tribe maintained legal ownership, the city’s power and influence often overshadowed tribal sovereignty, leading to tensions. The tribe’s interests were sidelined as the city prioritized profit and expansion, using tribal land for redevelopment while disregarding the rights of the residents and the tribe itself.

The city of Palm Springs used the Agua Caliente Tribe’s ownership of Section 14 to justify the demolitions, framing it as a legal loophole. Since the land was under federal trust and leased to non-tribal residents, the city argued that they had limited responsibility for improving infrastructure or protecting tenants’ rights. They claimed that the land could be better utilized for development, benefiting both the city and the tribe financially. By positioning the demolitions as a way to “revitalize” tribal land, the city masked its racially discriminatory agenda under the guise of economic progress, exploiting the tribe’s ownership to legitimize the forced evictions and destruction of homes.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The Impact on Displaced Communities

The long-term effects on former residents of Section 14 were devastating. Displaced families faced increased poverty, as many lost not only their homes but also the opportunity to build generational wealth through property ownership. Forced into overcrowded, substandard housing elsewhere, they struggled to rebuild their lives in less supportive environments. The trauma of displacement, including the sudden loss of community and security, left deep emotional scars. For many, the erasure of Section 14 meant the loss of cultural identity and stability, while the economic and psychological impacts reverberated through generations, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality.

The destruction of Section 14 resulted in a profound loss of cultural and communal spaces for Black and Latino residents in Palm Springs. The neighborhood had been a hub for social life, with close-knit families, churches, businesses, and community gatherings that sustained cultural traditions. When homes were demolished, these residents lost not just their physical dwellings but also the shared spaces that fostered identity, support, and belonging. This erasure of a culturally vibrant community severed ties that connected generations, leaving Black and Latino residents without a central place to rebuild or maintain their heritage in the city.

Attempts at Reconciliation

In recent years, there have been modern efforts to acknowledge and memorialize the injustices of Section 14. Activists, historians, and descendants of displaced families have worked to preserve the memory of the community through public exhibitions, historical markers, and educational initiatives. These efforts aim to highlight the racial discrimination and forced evictions that occurred, ensuring that this painful chapter of Palm Springs’ history is not forgotten. Some local organizations have pushed for reparative measures, including community discussions and formal recognition by city officials. However, despite these efforts, full reconciliation and restitution for the former residents and their families remain elusive.

Activism for reparations and recognition of the harms caused by the forced evictions in Section 14 has gained momentum in recent years. Community leaders, descendants of displaced families, and civil rights advocates have called for formal apologies, financial reparations, and memorials to honor the victims. They argue that the city should compensate families for the generational wealth and stability lost due to the demolitions. Activists have also demanded that Palm Springs acknowledge its role in perpetuating racial injustice and take tangible steps to address the long-lasting impact on Black and Latino communities, though progress toward meaningful reparations remains slow.

Section 14 in the Context of Broader Urban Erasure

Parallels to Other Instances of Urban Renewal

The forced evictions in Palm Springs’ Section 14 parallel other racially motivated displacements in U.S. cities, such as Tulsa’s Greenwood District and Los Angeles’ Chavez Ravine. In 1921, Greenwood, a thriving Black community in Tulsa, was destroyed during the Tulsa Race Massacre, wiping out homes, businesses, and generational wealth. Similarly, Chavez Ravine, a predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood, was demolished in the 1950s under the guise of urban renewal, displacing residents to make way for Dodger Stadium. Like Section 14, both communities were erased to benefit affluent, predominantly white interests, highlighting a pattern of using “urban development” as a tool to displace marginalized groups and strip them of wealth and community.

Broader Systemic Issues

The story of Section 14 is emblematic of broader systemic racism in housing, urban planning, and economic policies across the U.S. Like many marginalized communities, Section 14’s Black and Latino residents were segregated into underdeveloped areas, denied access to property ownership, and excluded from the city’s wealth. The city’s deliberate use of redevelopment to displace these residents reflects a national pattern where economic and urban planning decisions disproportionately harm communities of color. These practices perpetuate racial inequality, stripping marginalized groups of housing stability, generational wealth, and community resources, while prioritizing white, affluent interests under the guise of progress.

The displacement of Section 14 connects directly to modern-day gentrification and housing inequality. Similar to how Section 14 was cleared for profit-driven redevelopment, today’s gentrification displaces low-income, predominantly minority communities in favor of affluent residents and businesses. Rising property values, redevelopment, and luxury projects push out long-standing residents, erasing cultural identities and deepening economic divides. Housing inequality persists as these displaced communities struggle to afford new homes, while wealthier groups benefit from revitalized areas. Section 14’s legacy mirrors the ongoing cycle of urban displacement, where economic gain trumps the rights and stability of marginalized populations.

Modern-Day Palm Springs and Continuing Injustices

Palm Springs Today

Today, Palm Springs thrives as a premier tourist destination, fueled by luxury resorts, golf courses, and a vibrant arts scene. The city’s economy flourishes through high-end real estate development, festivals like Coachella, and its appeal as a desert getaway for the wealthy. Despite this prosperity, the benefits largely favor affluent visitors and residents, while the city’s history of racial and economic inequality, exemplified by the erasure of Section 14, remains overlooked. The focus on tourism and upscale development continues to overshadow efforts to address the lingering effects of past injustices on marginalized communities.

The history of Section 14 remains largely unrecognized in Palm Springs’ official narrative. While the city celebrates its status as a luxurious tourist destination, the forced displacement and erasure of its Black and Latino community in Section 14 are rarely acknowledged in public discourse or local history. Monuments and commemorations focus on the city’s glamorous past, overlooking the racial injustices that shaped its development. This selective memory perpetuates the invisibility of Section 14’s residents, leaving their stories of eviction and loss absent from the city’s identity and broader historical record.

Contemporary Struggles

Racial inequality, housing insecurity, and displacement remain pressing issues in the Palm Springs region. Rising property values and gentrification continue to disproportionately impact Black, Latino, and Native American residents, pushing them out of the city’s more desirable areas. Affordable housing is scarce, and many low-income families struggle to stay in their homes as the city prioritizes upscale development. These challenges echo the historical displacement of Section 14, with marginalized communities still facing economic exclusion, limited access to housing, and systemic barriers that perpetuate cycles of inequality and displacement in the region.

Local organizations in Palm Springs are working to ensure the history of Section 14 is not forgotten. Through public events, historical exhibitions, and educational outreach, these groups aim to raise awareness about the forced evictions and the racial injustices that occurred. Some advocate for the inclusion of Section 14’s story in school curricula and city planning discussions, while others push for memorials and public recognition. These efforts seek to preserve the memory of the displaced communities and challenge the city’s selective historical narrative, striving to honor the legacy of those affected by the erasure of Section 14.

Remembering the racial injustices of Section 14 is crucial to understanding the broader history of inequality in Palm Springs and the United States. The forced evictions and destruction of this vibrant Black and Latino community exemplify the systemic racism embedded in urban development and housing policies. By acknowledging this painful past, we honor the resilience of those who suffered and lost their homes, and we ensure their stories are not erased. Reflecting on Section 14’s history reminds us of the ongoing struggles for racial and economic justice, and the importance of confronting these legacies to prevent further injustice.

A historical reckoning with Section 14 is vital for achieving reparative justice and confronting systemic racism in urban planning. Acknowledging past injustices is the first step in addressing the deep-rooted racial and economic inequalities that persist today. Reparative justice—whether through financial compensation, public recognition, or community support—must be pursued to right these historical wrongs. Urban planning policies should prioritize inclusion, ensuring marginalized communities are not sacrificed for profit-driven development. By confronting these systemic issues, cities like Palm Springs can move toward a more just and equitable future, where all residents are valued and protected.

The legacy of Section 14 reflects broader patterns of racial injustice in America, particularly in housing and urban development. Like many communities of color across the country, Section 14’s residents were systematically displaced to make way for profit-driven redevelopment, highlighting the recurring use of urban planning as a tool for racial and economic exclusion. This history mirrors the struggles of other marginalized groups who faced similar fates, demonstrating how racial discrimination in housing policies has long stripped minority communities of stability and opportunity. Section 14 serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing need for reform in how cities prioritize development, equity, and justice.

Sources and Further Reading

Books:

- “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America” by Richard Rothstein

- This seminal book provides a comprehensive look at how racial segregation in housing was systematically enforced by government policies, offering context for understanding Section 14 in Palm Springs. Rothstein explores the structural racism behind zoning laws, housing covenants, and redevelopment projects, illuminating broader patterns that directly relate to the forced evictions in Section 14.

- “City of Segregation: 100 Years of Struggle for Housing in Los Angeles” by Andrea Gibbons

- Gibbons details the history of racial segregation and housing struggles in Los Angeles, providing a lens through which to view Palm Springs’ own policies. Though focused on L.A., this book underscores the legal and political battles that shaped many cities, including Palm Springs, where Section 14’s residents fought against unjust urban redevelopment.

- “Black and Brown in Los Angeles: Beyond Conflict and Coalition” edited by Josh Kun and Laura Pulido

- This collection examines the experiences of Black and Latino communities in Southern California, drawing parallels to the communities that lived in Section 14. The book provides historical, social, and political perspectives on the racial dynamics that influenced urban policies across Southern California.

- “White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism” by Kevin M. Kruse

- While focused on Atlanta, this book highlights how white suburbanization and urban flight influenced city planning and redevelopment across the U.S., offering insights into how Palm Springs’ affluent white residents and developers used similar tactics to displace communities of color, like those in Section 14.

- “The Bulldozer and the Big Tent: Blind Republicans, Lame Democrats, and the Recovery of American Ideals” by Todd Gitlin

- Gitlin examines post-World War II urban development policies, highlighting the political maneuvering behind projects that displaced marginalized communities. His insights provide a backdrop for understanding how political forces shaped the destruction of Section 14.

Articles:

- “Palm Springs: Paradise Lost for Section 14 Residents” by Nathan Solis, Los Angeles Times

- This article provides a historical overview of the forced evictions in Section 14, using personal stories and interviews to highlight the human impact of the city’s redevelopment efforts. It also discusses modern efforts to acknowledge and memorialize the lost community.

- “Erasing Section 14: Racism and Urban Renewal in Palm Springs” by Anthony A. Lee, The Journal of California Anthropology

- Lee’s article offers a detailed anthropological and historical study of Section 14, analyzing the intersection of race, land use, and urban planning in Palm Springs. The article focuses on the displacement and erasure of Black and Latino communities.

- “Bulldozers and Fire: The Destruction of Section 14 in Palm Springs” by Paige Osborne, KCET (PBS)

- This investigative piece looks at the systematic destruction of Section 14, focusing on the city’s use of bulldozers and fire to clear the land. It also covers the aftermath, including legal battles and modern-day activism.

- “Remembering Section 14” by Lisa Napoli, The Desert Sun

- A deep dive into the personal stories of former Section 14 residents, this article examines the emotional and psychological toll of displacement, while also highlighting current efforts to honor the legacy of the community.

Documentaries and Interviews:

- “Section 14: The Other Palm Springs” directed by Eduard Cáceres

- This documentary focuses on the history of Section 14 and the struggles of its residents, using archival footage, interviews with survivors, and historians’ perspectives to tell the story of the neighborhood’s destruction and the fight for justice.

- “The City of Palm Springs and Section 14” (PBS Southern California)

- This PBS special explores the racial tensions, policies, and political forces that led to the forced evictions in Section 14. Interviews with historians, civil rights leaders, and descendants of displaced families offer rich context for understanding the broader civil rights implications.

- “Palm Springs Black History” – Oral History Project

- A collection of oral histories from Black residents of Palm Springs, this project documents the experiences of those who lived through the evictions in Section 14. Their stories provide firsthand accounts of the social, cultural, and economic impact of the displacement.

- “Dodger Stadium: Chavez Ravine and Urban Displacement” directed by Paul Espinosa

- While focused on Chavez Ravine, this documentary provides important parallels to the Section 14 story. It examines how low-income Latino residents were displaced to make way for Dodger Stadium, mirroring the forced removals in Palm Springs.

Academic Papers and Theses:

- “Urban Renewal or Racial Erasure: A Case Study of Section 14” by Danielle Smith, University of California, Riverside

- This thesis provides an in-depth analysis of Section 14’s destruction through the lens of urban renewal policies, race, and power dynamics in mid-20th century California. It also considers the long-term consequences for displaced residents.

- “Racial Zoning and Palm Springs: Examining Section 14’s Legacy” by Michael Davis, Claremont Graduate University

- Davis’ research focuses on how racial zoning laws and discriminatory policies facilitated the destruction of Section 14, connecting these practices to national patterns of housing inequality.

Further Historical Context on Urban Displacement and Civil Rights:

- “The Color of Law” (Documentary Series)

- A companion to Richard Rothstein’s book, this series delves into how government policies created racially segregated neighborhoods across the U.S., with specific episodes addressing the experiences of Black and Latino communities in California.

- “Eyes on the Prize” (PBS)

- While not specific to Palm Springs, this iconic documentary series on the civil rights movement offers important context for understanding the broader struggle for racial justice, including battles over housing and urban development.

- “The History of Racial Displacement in America” – NPR Podcast

- This podcast episode explores how cities across the U.S. systematically displaced minority communities under the guise of urban renewal. It draws comparisons between Section 14, Tulsa’s Greenwood District, and Chavez Ravine.

By incorporating these sources and materials, readers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the history of Section 14 and its broader implications for racial justice, urban planning, and civil rights in the United States.

Leave a Reply